As I'm in mega-blogging mode at the mode, let's pop a rough cut on here. Words from a rather good write-up on UCP, (just to keep the Samm copyright police quiet. :

One of the first specialist manufacturers to build a Group C racer was Peter Sauber. This Swiss engineer and motor racing enthusiast previously constructed mainly small-engined sports-prototypes, so Group C was quite a step forward. He had teamed up with engine specialist Heini Mader and together they created the Cosworth engined Sauber C6 in 1982. The car looked very purposeful, but the badly vibrating V8 engine proved to be a reliability nightmare. In the following seasons, the Swiss team had a little more success with the BMW engined C7, but they could not match the Works developed Porsches and Lancias. The C7's biggest achievement was a ninth at Le Mans in 1983; preventing a complete Porsche top-ten. Perhaps with the intention of securing factory backing, Peter Sauber asked Mercedes-Benz if he could use their brand new windtunnel to test his latest racing car. The Germans were clearly impressed and shortly after the wind tunnel test an exclusive engine deal was signed between Sauber and Mercedes. This effectively meant the return of Mercedes-Benz to sportscar racing for the first time since their withdrawal after the tragic 1955 Le Mans. The priority was to develop a race winning engine first before drawing too much attention and in the first few years of the cooperation, Mercedes-Benz was listed as an engine supplier only.

Sauber was particularly interested in the recently introduced, all-alloy five litre V8 engine, known internally as the M117. Mader was commissioned to turn this street engine into a full Group C powerplant by adding two KKK Turbochargers. With Group C fuel limitations in mind, the engine was not only developed for outright performance, but also to get sufficient mileage. In qualifying trim the engine easily produced 700 - 800 bhp, but in racing spec 650 bhp was the more sensible output. The newly developed twin-Turbo V8 was mated to a familiar Hewland five speed gearbox. For the first Sauber Mercedes, the C8, Peter Sauber used the C7's aluminium monocoque as a basis. The Mercedes engine was mounted in a steel subframe directly behind the driver's compartment. All the other running gear was very conventional with independent suspension and vented discs all-round. Subject of the windtunnel test, the ground-effects body was indeed very efficient, although not very stable. At Le Mans in 1985 the sole Sauber Mercedes C8 entered recorded the second highest top speed, but also flipped on the Hunaudieres in practice. Although the car landed on its wheels, it was damaged too much to start the race.

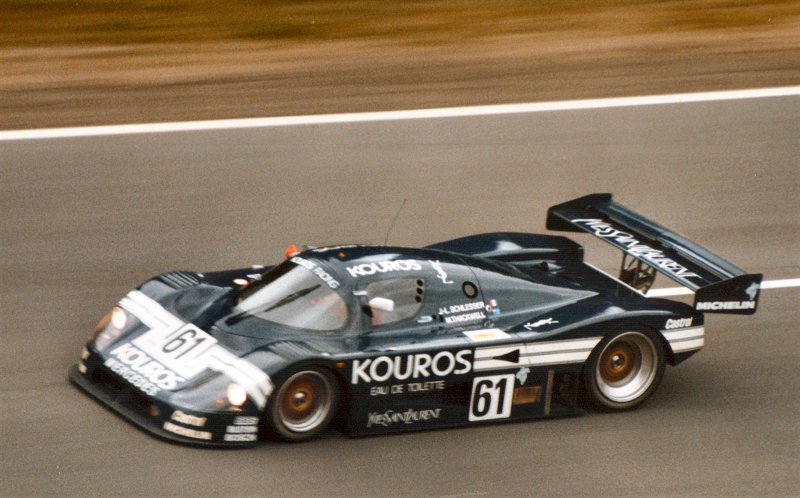

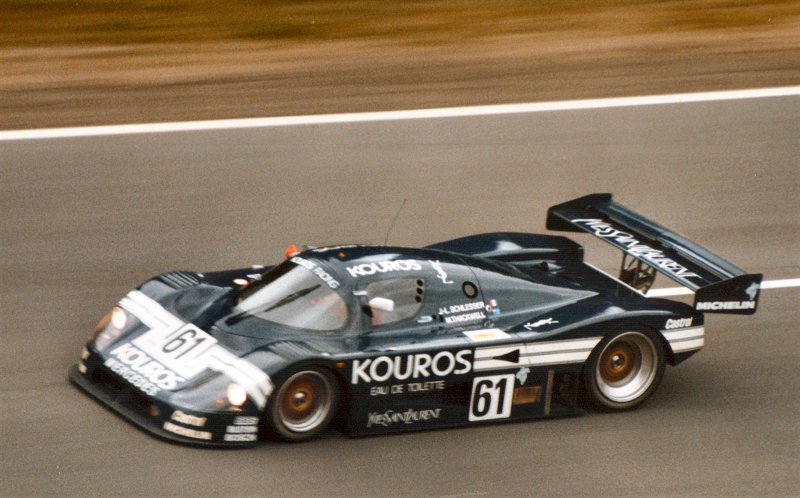

The Sauber team returned the following year with two new C8 chassis, livered in the dark blue Kouros colours. Both cars managed to start the race, but retired with engine and gearbox problems before night fell. Tweaks to the aerodynamics had made the cars more stable on the straights, but they weren't quite as fast as in 1985. One of the C8s was sold to privateer Noel del Bello, while Sauber and Mercedes were busy working on a replacement for the 1987 season. The C8 was raced twice more at Le Mans by the Frenchman, but again with little success.Logically dubbed the C9, the 1987 Sauber racer was again a development of its predecessor, modified in detail only. The rear suspension and the body were brand new, whereas the engine was a further Mader development. The Saubers made a better impression at Le Mans in 1987, qualifying seventh and eight. In the opening stages of the race, Johnny Dumfries was running as high as fourth before retiring with a gearbox problem after only 37 laps. The second car faired not much better, eventually succumbing to its second drivetrain related problems at around midnight.

Surprisingly Mercedes-Benz was not deterred and dramatically upped their involvement in 1988 to full factory backing. This paid off immediately as a Sauber Mercedes C9 was driven to victory in the Jerez 800 km, one lap clear of the dominant Jaguars. That year's Le Mans was an even bigger than the previous editions with both C9s forced to be withdrawn before the start. The combination of higher speeds and higher downforce had increased the loads on the tires too much, causing the rear tires to burst on one of the C9s at very high speed during qualifying. Starting the race was considered too dangerous. For 1989 Mercedes-Benz provided a completely new development of the alloy V8 engine, known as the M119. The biggest change was a full four valve head with double overhead camshafts. This bumped the power to 720 bhp and 810 Nm in race spec. The new quad-cam V8 engine was fitted to the proven C9 chassis. The Germans' involvement in the Sauber program was visibly increased as the cars were now painted silver; a clear drawback to the successful Silver Arrows of years past.

For the fifth Sauber Mercedes attempt, the team again fielded two cars. All of the four difficult previous editions were quickly forgotten as the two cars were placed first and second on the grid. After a trouble free race, the two cars crossed the line in the opposite order, clinching a convincing one-two victory. The winning C9 was driven by Jochen Mass, Manuel Reuter and Stanley Dickens. The team kept the Le Mans winning form for that season's World Championship and with seven wins out of eight races, they were CROWNed World Champions at the end of the season. Encouraged by the good results, Sauber developed a brand new car for 1990. The aluminium monocoque was replaced by a more modern and rigid carbon fibre one. The C10 name was skipped because it was difficult to pronounce in German, so the new car was dubbed C11. Much of the running gear, including the M119 engine, was carried over from the C9. Surprisingly, the Swiss/German team did not return to Le Mans and instead focused on defending the World Championship. They did so with visible ease, with the last race of the season being won by Jochen Mass and a young Michael Schumacher.

For the 1991 season Sauber developed the flat-12 engined C291,

in accordance with the new F1 inspired 3.5 litre Group C regulations. Nevertheless, the C11 was brought back from retirement for Le Mans, but the flawless race of 1989 proved to be the rare exception as all three 'Silver Arrows' fielded retired with mechanical issues. At the end of the season, both Sauber and Mercedes-Benz withdrew from sportscar racing, to focus in Formula 1.

One of the first specialist manufacturers to build a Group C racer was Peter Sauber. This Swiss engineer and motor racing enthusiast previously constructed mainly small-engined sports-prototypes, so Group C was quite a step forward. He had teamed up with engine specialist Heini Mader and together they created the Cosworth engined Sauber C6 in 1982. The car looked very purposeful, but the badly vibrating V8 engine proved to be a reliability nightmare. In the following seasons, the Swiss team had a little more success with the BMW engined C7, but they could not match the Works developed Porsches and Lancias. The C7's biggest achievement was a ninth at Le Mans in 1983; preventing a complete Porsche top-ten. Perhaps with the intention of securing factory backing, Peter Sauber asked Mercedes-Benz if he could use their brand new windtunnel to test his latest racing car. The Germans were clearly impressed and shortly after the wind tunnel test an exclusive engine deal was signed between Sauber and Mercedes. This effectively meant the return of Mercedes-Benz to sportscar racing for the first time since their withdrawal after the tragic 1955 Le Mans. The priority was to develop a race winning engine first before drawing too much attention and in the first few years of the cooperation, Mercedes-Benz was listed as an engine supplier only.

Sauber was particularly interested in the recently introduced, all-alloy five litre V8 engine, known internally as the M117. Mader was commissioned to turn this street engine into a full Group C powerplant by adding two KKK Turbochargers. With Group C fuel limitations in mind, the engine was not only developed for outright performance, but also to get sufficient mileage. In qualifying trim the engine easily produced 700 - 800 bhp, but in racing spec 650 bhp was the more sensible output. The newly developed twin-Turbo V8 was mated to a familiar Hewland five speed gearbox. For the first Sauber Mercedes, the C8, Peter Sauber used the C7's aluminium monocoque as a basis. The Mercedes engine was mounted in a steel subframe directly behind the driver's compartment. All the other running gear was very conventional with independent suspension and vented discs all-round. Subject of the windtunnel test, the ground-effects body was indeed very efficient, although not very stable. At Le Mans in 1985 the sole Sauber Mercedes C8 entered recorded the second highest top speed, but also flipped on the Hunaudieres in practice. Although the car landed on its wheels, it was damaged too much to start the race.

The Sauber team returned the following year with two new C8 chassis, livered in the dark blue Kouros colours. Both cars managed to start the race, but retired with engine and gearbox problems before night fell. Tweaks to the aerodynamics had made the cars more stable on the straights, but they weren't quite as fast as in 1985. One of the C8s was sold to privateer Noel del Bello, while Sauber and Mercedes were busy working on a replacement for the 1987 season. The C8 was raced twice more at Le Mans by the Frenchman, but again with little success.Logically dubbed the C9, the 1987 Sauber racer was again a development of its predecessor, modified in detail only. The rear suspension and the body were brand new, whereas the engine was a further Mader development. The Saubers made a better impression at Le Mans in 1987, qualifying seventh and eight. In the opening stages of the race, Johnny Dumfries was running as high as fourth before retiring with a gearbox problem after only 37 laps. The second car faired not much better, eventually succumbing to its second drivetrain related problems at around midnight.

Surprisingly Mercedes-Benz was not deterred and dramatically upped their involvement in 1988 to full factory backing. This paid off immediately as a Sauber Mercedes C9 was driven to victory in the Jerez 800 km, one lap clear of the dominant Jaguars. That year's Le Mans was an even bigger than the previous editions with both C9s forced to be withdrawn before the start. The combination of higher speeds and higher downforce had increased the loads on the tires too much, causing the rear tires to burst on one of the C9s at very high speed during qualifying. Starting the race was considered too dangerous. For 1989 Mercedes-Benz provided a completely new development of the alloy V8 engine, known as the M119. The biggest change was a full four valve head with double overhead camshafts. This bumped the power to 720 bhp and 810 Nm in race spec. The new quad-cam V8 engine was fitted to the proven C9 chassis. The Germans' involvement in the Sauber program was visibly increased as the cars were now painted silver; a clear drawback to the successful Silver Arrows of years past.

For the fifth Sauber Mercedes attempt, the team again fielded two cars. All of the four difficult previous editions were quickly forgotten as the two cars were placed first and second on the grid. After a trouble free race, the two cars crossed the line in the opposite order, clinching a convincing one-two victory. The winning C9 was driven by Jochen Mass, Manuel Reuter and Stanley Dickens. The team kept the Le Mans winning form for that season's World Championship and with seven wins out of eight races, they were CROWNed World Champions at the end of the season. Encouraged by the good results, Sauber developed a brand new car for 1990. The aluminium monocoque was replaced by a more modern and rigid carbon fibre one. The C10 name was skipped because it was difficult to pronounce in German, so the new car was dubbed C11. Much of the running gear, including the M119 engine, was carried over from the C9. Surprisingly, the Swiss/German team did not return to Le Mans and instead focused on defending the World Championship. They did so with visible ease, with the last race of the season being won by Jochen Mass and a young Michael Schumacher.

For the 1991 season Sauber developed the flat-12 engined C291,

in accordance with the new F1 inspired 3.5 litre Group C regulations. Nevertheless, the C11 was brought back from retirement for Le Mans, but the flawless race of 1989 proved to be the rare exception as all three 'Silver Arrows' fielded retired with mechanical issues. At the end of the season, both Sauber and Mercedes-Benz withdrew from sportscar racing, to focus in Formula 1.